2.3 Molecular orbitals

(a) What are molecular orbitals? How do you calculate them?

(b) What are the Roothaan equations? What is the Hückel model?

2.4 The molecular ion H2+

The molecular ion H2+ consists of one electron and two protons.

(a) Explain the Born-Oppenheimer approximation. What is the Schrödinger equation for the electron when the Born-Oppenheimer approximation is used?

(b) Assuming that the wave function can be expressed as a linear combination of atomic orbitals of the form $\psi=c_1\phi_{\text{1s}}(\vec{r}-\vec{r}_A) +c_2\phi_{\text{1s}}(\vec{r}-\vec{r}_B)$, construct the two molecular orbitals and plot them.

(c) Consider the case that the protons are moved far apart. What are the values of the energies of the two molecular orbitals in this limit?

(d) Draw the potential energy of the electron along the interatomic axis under the assumption that the bond length is 1.06 Å.

2.5 Homonuclear diatomic molecules

Homonuclear diatomic molecules consist of two atoms of the same type like H2, N2 or O2. The molecular orbitals of all homonuclear diatomic molecules have the same form as for H2; only the effective nuclear charge differs. The energies of the first few molecular orbitals for homonuclear diatomic molecules are ordered $1\sigma_g \lt 1\sigma_u \lt 2\sigma_g \lt 2\sigma_u \lt 3\sigma_g \approx 1\pi_u \lt 1\pi_g \lt 3\sigma_u$. The $\sigma$ orbitals are singly degenerate (they can hold 2 electrons) but the $\pi$ orbitals are doubly degenerate (they can hold 4 electrons). $1\pi_u$ is lower in energy than $3\sigma_g$ up to and including N2 but $3\sigma_g$ is lower in energy for atoms with more electrons than nitrogen.

Specify the ground state of H2, N2, Li2+, Be2, C2, and O2.

H2: $1\sigma_g^2$

N2: $1\sigma_g^2 \, 1\sigma_u^2 \, 2\sigma_g^2 \, 2\sigma_u^2 \, 1\pi_u^4 \, 3\sigma_g^2$

Li2+: $1\sigma_g^2 \, 1\sigma_u^2 \, 2\sigma_g^1 $

Be2: $1\sigma_g^2 \, 1\sigma_u^2 \, 2\sigma_g^2 \, 2\sigma_u^2 $

C2: $1\sigma_g^2 \, 1\sigma_u^2 \, 2\sigma_g^2 \, 2\sigma_u^2 \, 1\pi_u^4 $

O2: $1\sigma_g^2 \, 1\sigma_u^2 \, 2\sigma_g^2 \, 2\sigma_u^2 \, 3\sigma_g^2\, 1\pi_u^4 \, 1\pi_g^2$

2.6 Linear combination of atomic orbitals

A linear combination of atomic orbitals used to find the molecular orbitals of a He2 molecule contains four atomic orbitals,

\[ \begin{equation} \psi(\vec{r})= c_1\phi^{Z=2}_{\text{1s}}\left(\vec{r}-\vec{r}_{\text{He1}}\right)+c_2\phi^{Z=2}_{\text{1s}}\left(\vec{r}-\vec{r}_{\text{He2}}\right)+c_3\phi^{Z=2}_{\text{2s}}\left(\vec{r}-\vec{r}_{\text{He1}}\right)+c_4\phi^{Z=2}_{\text{2s}}\left(\vec{r}-\vec{r}_{\text{He2}}\right). \end{equation} \]What is the integral that needs to be evaluated to determine the Hamiltonian matrix element $H_{12}$ for this molecule? What is the integral that needs to be evaluated to determine the matrix element of the overlap matrix $S_{13}$ in the Roothaan equations? This integral is easy to evaluate. What is $S_{13}$?

2.7 Molecular databases

Use a database (such as the one embedded in jmol) to determine the Si-O bond length and the angle formed by the atoms Si-O-C in tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS).

2.8 Conjugated rings and conjugated chains

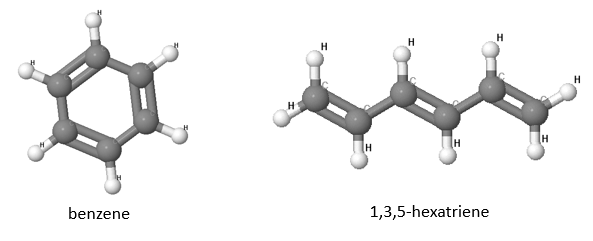

Aromatic molecules are substances which are chemically unreactive. In this exercise, we will compare the prototypical aromatic molecule benzene with its linear chain equivalent, 1,3,5-hexatriene (shown in the picture below).

(a) How many $p_z$ electrons are in these two molecules?

(b) Set up the Roothaan-equations for both molecules assuming that only the $p_z$ orbitals need to be included. Look at the discussion of molecular orbitals of a conjugated rings and the molecular orbitals of conjugate chains. Use $H_{11} = - 12$ eV, $H_{12} = -3.8$ eV, $S_{11} = 1$, and $S_{12} = 0.27$. These are not the values that the simple model gives but are close to the observed values.

(c) Which molecular orbitals will be occupied for benzene and for 1,3,5-hexatriene? Which molecular orbitals are degenerate? (Degenerate molecular orbitals have the same energy).

(d) The total energy of the molecules can be approximated as the sum over all occupied molecular orbitals. Which molecule has the lower energy?

(e) Calculate and compare the energy difference between the highest occupied molecular orbital and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital for both molecules. This energy difference could be measured spectroscopically.

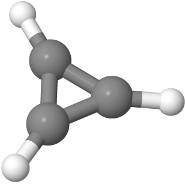

2.9 Cyclopropene

The cation of cyclopropene is the smallest aromatic molecule. The Roothaan equations can be used to express three molecular orbitals in terms of the three $2p_z$ orbitals. Use $H_{11} = - 12$ eV, $H_{12} = -3.8$ eV, $S_{11} = 1$, and $S_{12} = 0.27$.

(a) The cation of cyclopropene has one less electron than neutral cyclopropene. How many electrons are in the cation in total? How many electrons are in the molecular $\pi$-system and have to be accounted for in the Roothaan equations?

(b) Calculate the energies of the orbitals. What is the degeneracy of the unoccupied orbitals?

(c) The molecule can absorb a photon to promote one electron from the highest occupied molecular orbital to the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital. What is the wavelength of the photon?

2.10 H2 and He2

Atomic orbitals are often used to construct trial wavefunctions that solve a molecular orbital Hamiltonian. In the simplest approximation where we neglect the electron-electron interactions, we can use the molecular orbitals of H2+ to estimate the ground state energies of H2 and He2.

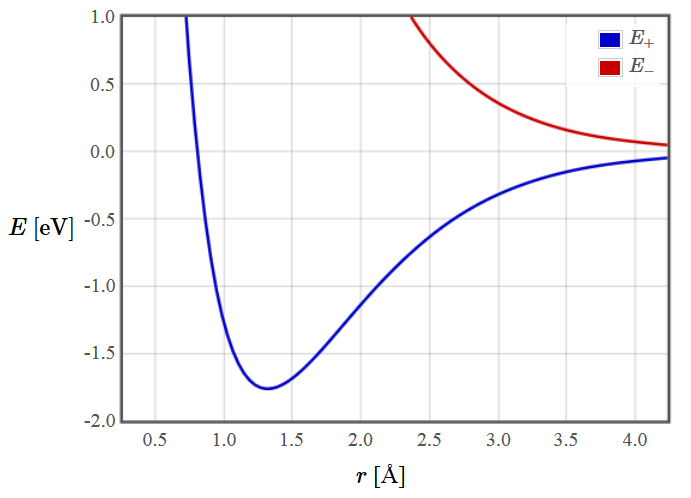

The energies of the two lowest molecular orbitals of H2+ are shown in the plot below.

If the atoms are moved far apart, we obtain the energy of two isolated atoms with an energy of zero.

(a) How many molecular orbitals are occupied for H2 and for He2?

(b) Compare the energies of H2 and He2 as a function of interatomic distance. Explain why one of these molecules is more stable than the other.

2.11 Effective nuclear charge

Atomic orbitals are often used to construct trial wavefunctions that solve a molecular orbital Hamiltonian. To include the effects of electron shielding, an effective nuclear charge is often introduced. The form of the 1s orbital with an effective nuclear charge is,

$$\phi_{\text{1s}}=\sqrt{\frac{Z_{eff}^3}{\pi a_0^3}}\exp\left(-\frac{Z_{eff}r}{a_0}\right),$$where $Z_{eff}$ is the effective charge of the nucleus. The appropriate effective charge to use is given in the table of Slater's rules.

Consider H2 and He2. How many molecular orbitals are occupied for each of these molecules? The molecular orbital energies are calculated as for H2+,

\begin{equation} E_{+}= \frac{H_{11}+ H_{12}}{1+ S_{12}}, \qquad E_{-}= \frac{H_{11}- H_{12}}{1- S_{12}}. \end{equation}Use the programs of the page Molecular orbitals of the molecular ion H2+ to calculate $H_{11}$, $H_{12}$, $S_{12}$, $E_+$ and $E_-$ for the protons far apart and at the bond length of H2, 0.074 nm. When the atoms are far apart, the energy of the two isolated H atoms is $2H_{11}$. Compare this to the energy of both electrons in the $\psi_{+}$ orbital at the bond length of H2. Do the same for He2 $(Z_{eff} = 1.7)$. The bond length of He2 is 0.3 nm. What does this say about the bond strengths of H2 and He2? By including electron-electron interactions this calculation could be performed more accurately. This, however, would require a significant numerical effort and you don't have to do this.